Judges

The first black judge to have been appointed by the president to the federal bench was William Henry Hastie, whom Franklin Delano Roosevelt named as a district court judge for the U.S. Virgin Islands in 1937.

Mary McLeod Bethune was an extraordinary educator, civil rights leader, and government official who founded the National Council of Negro Women and Bethune-Cookman College. She was the first African American woman to be involved in the White House, assisting four different presidents.

Mary Jane McLeod was born on July 10, 1875, in Mayesville, South Carolina. The fifteenth of seventeen children, Mary's parents, as well as some of her older siblings, had been slaves. The family had a small farm and the entire family worked hard to make ends meet. Mary began to work in the fields at age five, and she took an early interest in her own education, seeing that as a way out of poverty.

When Mary was about eleven, the Mission Board of the Presbyterian Church opened a school for African-American children. It was about four miles from her home, and the children had to walk back and forth to school, but Mary wanted to go.

With the help of benefactors, Bethune attended Scotia Seminary in North Carolina hoping to become a missionary in Africa. However, she realized that "Africans in America needed Christ and school just as much as Negroes in Africa. My life work lay not in Africa but in my own country." From there she received a scholarship to the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, where she continued to be a high achiever. Mary was the only African-American student there, and one of only a few non-whites.

Ready to begin teaching Mary McLeod returned to Mayesville and taught for a year, leaving for a teaching position in Augusta, Georgia at Haines Institute. Mary's next stop was Sumter, South Carolina, where she taught for two years at Kendall Institute before marrying Albertus Bethune in 1898.

The couple moved to Savannah, Georgia, where Albertus had a new job. Mary did a little social work, but mainly she concentrated on raising her son, Albert, who was born in 1899. The marriage was not a success, although the couple remained together until 1907 and on good terms thereafter. Mary was restless, and she felt called to public service. A visiting minister from Palatka, Florida urged her to move there and manage the new mission school he was starting.

So in 1899 Mary Bethune moved to Florida with her son, followed by her husband. In Palatka she taught at the Mission School and visited prisoners in the county jail, reading and singing to them. She tried to help the prisoners in any way she could, and worked to free those who were not guilty. Because money was tight, Mary supplemented the family income by selling life insurance.

Mary Bethune wanted to provide opportunities for African-American girls, and to do this she would need a school. She hoped to build the school in a new area, and a minister suggested Daytona. Five years after arriving in Palatka, she moved to Daytona, Florida. Almost penniless, she was sheltered by a local woman recommended by the minister, who helped her find the house that she would use to open a school for African-American girls. This was her dream, and she worked to make it come true.

In 1904, Mary Bethune opened the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute for Negro Girls. The school opened with five girls as students and later accepted boys as well. Tuition was 50 cents a week, but Bethune never refused to educate a child whose parents could not afford the payment. Bethune worked not only to maintain the school, but she also fought aggressively the segregation and inequality facing blacks. There was objection from many at that time to the education of black children, but Bethune's zeal and dedication won over many skeptics of both races. She encouraged people to "Invest in the human soul. Who knows, it might be a diamond in the rough."

Mary Bethune also opened a high school and a hospital for blacks. She had immense faith in God and believed that nothing was impossible. Bethune remained president of the school for more than 40 years. In 1923, she oversaw the school's merger with the Cookman Institute, thereby forming the Bethune-Cookman College.

With her school a success, Mary Bethune became increasingly involved in political issues. It was through her discussions with Vice President Thomas Marshall that the Red Cross decided to integrate, and blacks were allowed to perform the same duties as whites. In 1917, she became president of the Florida Federation of Colored Women. In 1924, Bethune became president of the National Association of Colored Women, at that time the highest national office a black woman could aspire. And in 1935, she formed the National Council of Negro Women to take on the major national issues affecting blacks.

Mary Bethune gained national recognition in 1936, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed her director of African American affairs in the National Youth Administration and a special adviser on minority affairs. She served for eight years and supervised the development of employment opportunities and recreational facilities for African American youth throughout the United States. She also served as special assistant to the secretary of war during World War II. In the course of her government assignments she became a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt.

In 1974, Mrs. Bethune became the first Black leader and the first woman to have a monument, the Bethune Memorial Statue, erected on public park land in Washington DC in honor of her remarkable contributions. She also became the only Black woman to be honored with a memorial site in the nation's capital in 1994 when National Park Service acquired the Council House, Bethune's last official residence and the original headquarters of NCNW. Today the Council House offers a variety of educational programs and exhibits.

Don't miss a single page. Find everything you need on our complete sitemap directory.

Listen or read the top speeches from African Americans. Read more

Read about the great African Americans who fought in wars. Read more

African Americans invented many of the things we use today. Read more

Thin jazz, think art, think of great actors and find them here. Read more

Follow the history of Black Americans from slave ships to the presidency. Read more

Olympic winners, MVPS of every sport, and people who broke the color barrier. Read more

These men and women risked and sometimes lost their life to fight for the cause. Read more

Meet the people who worked to change the system from the inside. Read more

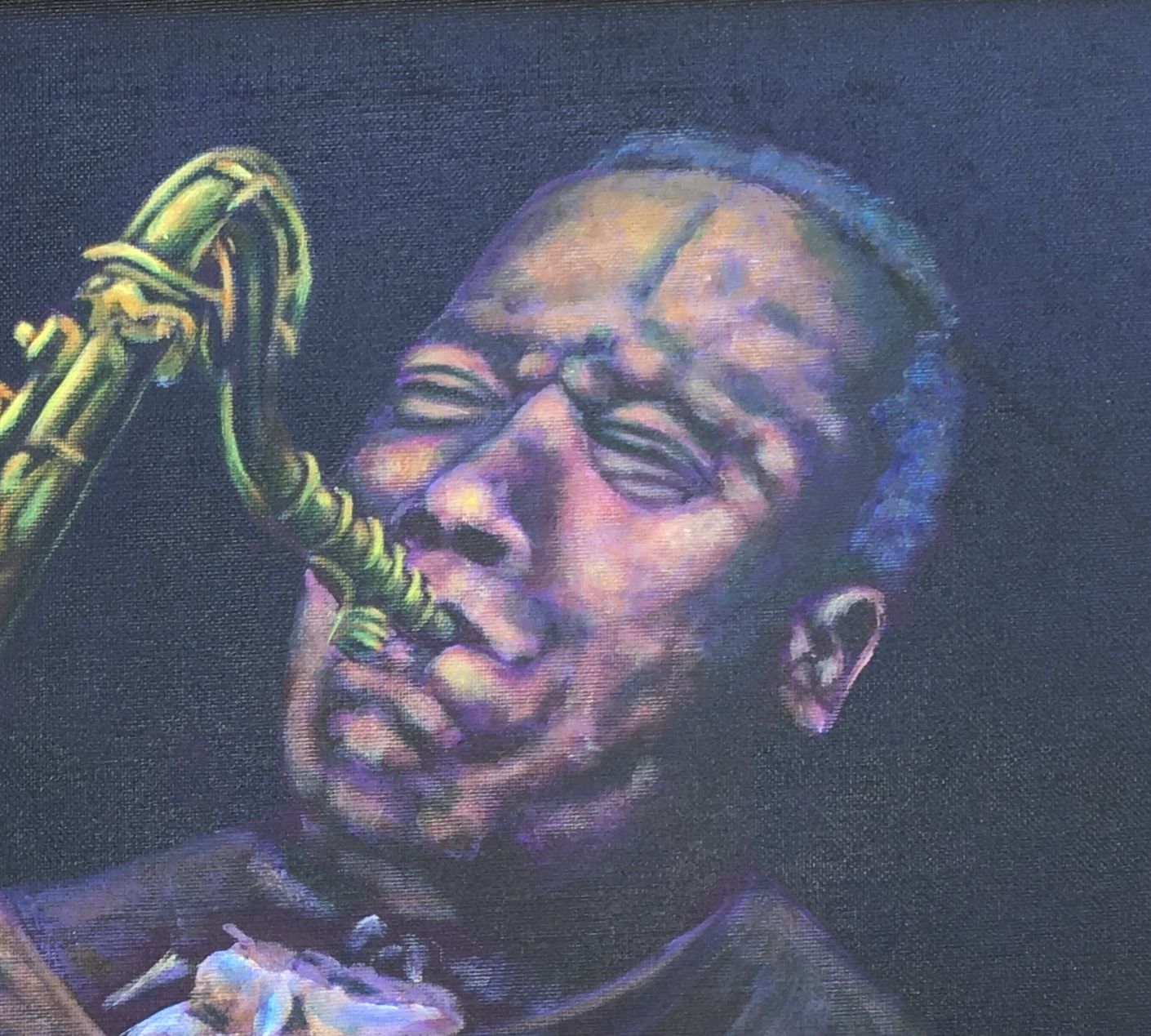

Visit my RedBubble page and use Michael Arnold Art to create greeting cards, T-shirts, mugs, and more.

The variety and impressive numbers of mammals, birds and marine wildlife in Alaska draw visitors from all over the world. For some travelers, Alaska is wilderness, at least compared to what they may know from back home. The pristine wilderness of Alaska is, perhaps, the last vestige of thriving populations of North American wildlife. Where else can you see polar bears, bald eagles, blue and humpbacked whales, gray wolves, grizzly bears, orcas, lynx, moose, and hundreds of other rare and endangered species in their original and undisturbed natural habitats?

Enjoy our website filled with original signed acrylic paintings by award winning Artist Michael Arnold. Located in Citrus County Florida, Michael Arnold is a the editor at the Citrus County Chronicle. When he's not busy being an editor, he is an avid artist who enjoys painting in a variety of styles. We hope you take the time to click on each image to see a larger view and to learn what the artist, Michael Arnold has to say about his paintings.

As dog owners and people who care deeply for animals and wildlife, we wanted our Dog Encyclopedia to be a website that could empower pet owners to create the most positive, loving environment for their dogs. Dog Encyclopedia realizes that owning a dog is like adding a new member to your family.

Floridian Nature has everything your are looking for in Florida nature. The wildlife of Florida is rich and varied, yet most of us are familiar with only a dozen or so species: the "well known endangered species such as manatees and panthers; those, like raccoons and squirrels, that have adapted to urban environments; the frightening alligators and black bears; and those like the armadillo who can't seem to cross the road. Yet they are just a few of the many animal species found in Florida.