Judges

The first black judge to have been appointed by the president to the federal bench was William Henry Hastie, whom Franklin Delano Roosevelt named as a district court judge for the U.S. Virgin Islands in 1937.

Benjamin Hooks was an African American civil rights leader. A Baptist minister and practicing attorney, he served as executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1977 to 1992, and throughout his career was a vocal campaigner for civil rights in the United States. Hooks was the first black to be appointed to the criminal court bench in his native Tennessee, and he was the first African-American to be named to the five-member Federal Communications Commission.

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, January 31, 1925, Benjamin Lawson Hooks grew up in the segregated South. He was the fifth of seven children of Robert B. Hooks and Bessie White Hooks. His father was a photographer and owned a photography studio with his brother Henry known at the time as Hooks Brothers, and the family was fairly comfortable by the standards of black people for the day.

Benjamin Hook’s paternal grandmother, Julia Britton Hooks, graduated from Berea College in Kentucky in 1874 and was only the second American black woman to graduate from college. She was a musical prodigy who began playing piano publicly at age five, and at age 18 joined Berea’s faculty. Her sister, Dr. Mary E. Britton, also attended Berea, and became a physician in Lexington, Kentucky. With such a family legacy, Benjamin Hooks was inspired to study hard and prepare himself for college. In his youth, he had felt called to the Christian ministry. His father, however, did not approve and discouraged him from such a calling.

In 1941 Benjamin Hooks enrolled in LeMoyne-Owen College, in Memphis, Tennessee, where he studied pre-law. In his college years he became more acutely aware that he was one of a large number of Americans who were required to use segregated lunch counters, water fountains, and restrooms. “I wish I could tell you every time I was on the highway and couldn’t use a restroom,” he told U.S. News & World Report in an interview. “My bladder is messed up because of that. Stomach is messed up from eating cold sandwiches.” Hooks went on to attend Howard University, where he graduated in 1944.

After graduation, Benjamin Hooks joined the Army and had the job of guarding Italian prisoners of war. He found it humiliating that the prisoners were allowed to eat in restaurants from which he was barred. He was discharged from the Army after the end of the war with the rank of staff sergeant.

After the war he enrolled at the DePaul University College of Law in Chicago to study law. No law school in his native Tennessee would admit him. He graduated from DePaul in 1948 with his Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree.

By 1949 Hooks had earned a local reputation as one of the few black lawyers in Memphis. At the Shelby County fair, he met a 24-year-old science teacher by the name of Frances Dancy. They began to date, and soon became inseparable. They were married in Memphis in 1952. Mrs. Hooks recalled in Ebony magazine that her husband was “good looking, very quiet, very intelligent.” She added: “He loved to go around to churches and that type of thing, so I started going with him. He was really a good catch.”

Benjamin Hooks still felt the calling to the Christian ministry that he had felt in his youth. He was ordained as a Baptist minister in 1956 and began to preach regularly at the Greater Middle Baptist Church in Memphis, while continuing his busy law practice. He joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference along with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He also became a pioneer in the NAACP-sponsored restaurant sit-ins and other boycotts of consumer items and services.

In addition to his other roles, Benjamin Hooks decided to enter Tennessee state politics and ran unsuccessfully for the state legislature in 1954 and for juvenile court judge in 1959 and 1963. Despite his losses, the personable young lawyer and preacher attracted not only black voters but liberal whites as well. By 1965 he was well enough known that Tennessee Governor Frank G. Clement appointed him to fill a vacancy in the Shelby County criminal court. With this he became the first black criminal court judge in Tennessee history. His temporary appointment to the bench expired in 1966 but he campaigned for, and won election to a full term in the same judicial office.

In 1972, Benjamin Hook became the first black commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission when President Richard Nixon> appointed him to that post. He pushed through a new rule requiring television and radio stations to be offered publicly before they could be sold; minority employment in the broadcast industry increase fivefold during his five-year tenure.

On November 6, 1976, the 64-member board of directors of the NAACP elected Benjamin Hooks executive director of the organization. By then, the membership had declined from a high of about 500,000 to only about 200,000. Hooks was determined to add to the enrollment and to raise money for the organization’s severely depleted treasury, without changing the NAACP’s goals or mandates. Under the leadership Of Benjamin Hooks, the N.A.A.C.P. faced a growing white backlash against school busing and affirmative action programs intended to redress past discrimination. And it repeatedly tangled with the administrations of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush to preserve the gains that minorities had made in the 1960s and ’70s. When Mr. Bush selected a conservative black federal judge, Clarence Thomas, to serve on the Supreme Court, the N.A.A.C.P. ultimately opposed the nomination.

I’ve had the misfortune of serving eight years under Reagan and three under Bush,” Mr. Hooks said in 1992, the year he stepped down as executive director. “It makes a great deal of difference about your expectations. We’ve had to get rid of a lot of programs we had hoped for, so we could fight to save what we already had.”

President George W. Bush awarded Benjamin Hooks the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, in November 2007. "As a civil rights activist, public servant and minister of the gospel, Dr. Hooks has extended the hand of fellowship throughout his years," Bush said. "It was not always an easy thing to do. But it was always the right thing to do".

Don't miss a single page. Find everything you need on our complete sitemap directory.

Listen or read the top speeches from African Americans. Read more

Read about the great African Americans who fought in wars. Read more

African Americans invented many of the things we use today. Read more

Thin jazz, think art, think of great actors and find them here. Read more

Follow the history of Black Americans from slave ships to the presidency. Read more

Olympic winners, MVPS of every sport, and people who broke the color barrier. Read more

These men and women risked and sometimes lost their life to fight for the cause. Read more

Meet the people who worked to change the system from the inside. Read more

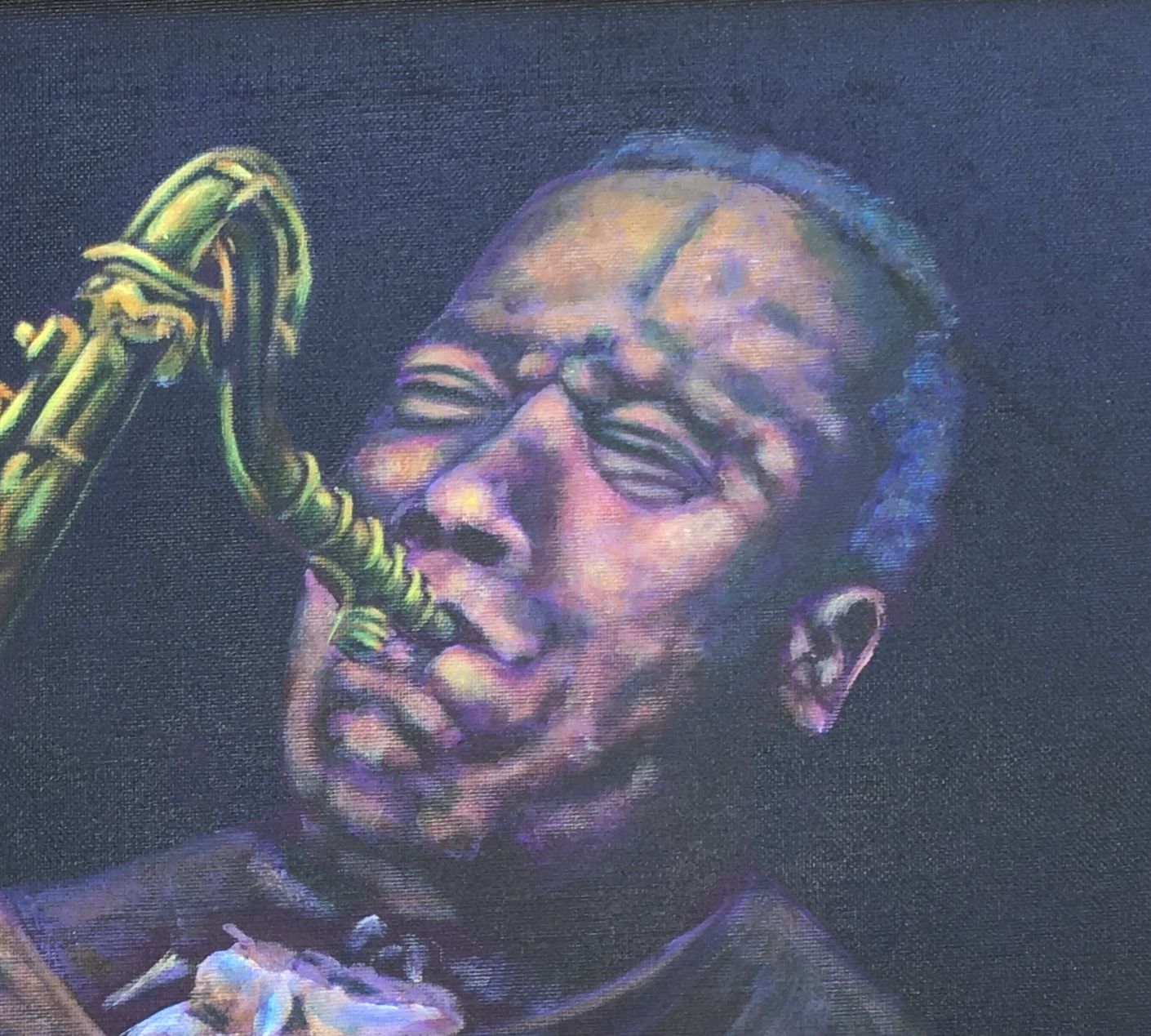

Visit my RedBubble page and use Michael Arnold Art to create greeting cards, T-shirts, mugs, and more.

The variety and impressive numbers of mammals, birds and marine wildlife in Alaska draw visitors from all over the world. For some travelers, Alaska is wilderness, at least compared to what they may know from back home. The pristine wilderness of Alaska is, perhaps, the last vestige of thriving populations of North American wildlife. Where else can you see polar bears, bald eagles, blue and humpbacked whales, gray wolves, grizzly bears, orcas, lynx, moose, and hundreds of other rare and endangered species in their original and undisturbed natural habitats?

Enjoy our website filled with original signed acrylic paintings by award winning Artist Michael Arnold. Located in Citrus County Florida, Michael Arnold is a the editor at the Citrus County Chronicle. When he's not busy being an editor, he is an avid artist who enjoys painting in a variety of styles. We hope you take the time to click on each image to see a larger view and to learn what the artist, Michael Arnold has to say about his paintings.

As dog owners and people who care deeply for animals and wildlife, we wanted our Dog Encyclopedia to be a website that could empower pet owners to create the most positive, loving environment for their dogs. Dog Encyclopedia realizes that owning a dog is like adding a new member to your family.

Floridian Nature has everything your are looking for in Florida nature. The wildlife of Florida is rich and varied, yet most of us are familiar with only a dozen or so species: the "well known endangered species such as manatees and panthers; those, like raccoons and squirrels, that have adapted to urban environments; the frightening alligators and black bears; and those like the armadillo who can't seem to cross the road. Yet they are just a few of the many animal species found in Florida.