The begining - Early Activists

After the Civil War blacks suffered greatly in the South. African Americans became targets for enraged white southerners. Lynchings killed hundreds of blacks every year.

Roy Innis was involved in the Harlem Congress of Racial Equality initiative, known as CORE, when fellow activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were murdered in 1964. He later went on to serve as the chairman of CORE, after which he mounted a vigorous campaign for establishment of an independent Board of Education for Harlem. Losing two sons to urban gun violence influenced Innis' views on crime and victims' rights so dramatically that he became one of the most vocal and active advocates of the Second Amendment rights, especially decent citizens' right of self-defense. Innis lectures throughout the United States and in foreign countries on gun issues.

Roy Emile Alfredo Innis was born June 6, 1934, in St. Croix, Virgin Islands. He was six years old when his father died, and in 1947 he moved to the United States, following his mother, who was sending for her children as money became available.

The shock of moving from the racially tolerant and predominantly black Virgin Islands to Harlem in New York City was tremendous. At that time discrimination against black Americans was commonplace. Innis attended the prestigious Stuyvesant High School in New York City, and in 1950, when he was 16 years old, he lied about his age and joined the U.S. Army. he received an honorable discharge two years later. On returning to New York, Innis earned his high school diploma and majored in chemistry at the City College of New York. After graduation Roy Innis worked as a researcher for the Vicks Chemical Company and had three children with his first wife, Violet.

After his first marriage ended, Innis fell in love with and married civil rights activist Doris Funnye. Funnye was active in the Harlem chapter of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality initiative. The Congress of Racial Equality had been founded in 1942 by six young Chicagoans as an interracial passive resistance organization. Led by longtime chairman James Farmer, CORE began by protesting discrimination in Chicago restaurants and grew to lead sit-ins at lunch counters in the South and sponsor the famous Freedom Rides that tested compliance with federal orders to desegregate bus lines. In 1964 Roy Innis was elected Chairman of the chapter’s education committee and advocated community-controlled education and black empowerment.

1964 was a tragic year for CORE. On June 21, 1964, three young civil rights workers from the Congress of Racial Equality initiative, a 21-year-old black Mississippian, James Chaney, and two white New Yorkers, Andrew Goodman, 20, and Michael Schwerner, 24 were brutally murdered in Mississippi. They had been working to register black voters in Mississippi during Freedom Summer and had gone to investigate the burning of a black church. They were arrested by the police on trumped-up charges, imprisoned for several hours, and then released after dark into the hands of the Ku Klux Klan, who beat and murdered them. It was later proven in court that a conspiracy existed between members of Neshoba County's law enforcement and the Ku Klux Klan to kill them.

The FBI arrested 18 men in October 1964, but state prosecutors refused to try the case, claiming lack of evidence. The federal government then stepped in, and the FBI arrested 18 in connection with the killings. In 1967, seven men were convicted on federal conspiracy charges and given sentences of three to ten years, but none served more than six. No one was tried on the charge or murder. The contemptible words of the presiding federal judge, William Cox, give an indication of Mississippi's version of justice at the time: "They killed one nigger, one Jew, and a white man. I gave them all what I thought they deserved."

On Jan. 7, 2005, four decades after the crime, Edgar Ray Killen, then 80, was charged with three counts of murder. He was accused of orchestrating the killings and assembling the mob that killed the three men. On June 21st, the 41st anniversary of the murders, Killen was convicted on three counts of manslaughter, a lesser charge. He received the maximum sentence, 60 years in prison. The grand jury declined to call for the arrest of the seven other living members of the original group of 18 suspects arrested in 1967.

Roy Innis went on to lead CORE’s fight for an independent Police Review Board to address cases of police brutality. In 1965, he was elected Chairman of Harlem CORE, after which he mounted a vigorous campaign for establishment of an independent Board of Education for Harlem. A proposition to this end was presented to the 1967 New York State Constitutional Convention.

It was during 1968 that Roy Innis drafted the Community Self Determination Bill of 1968, garnering bipartisan sponsorship of this bill by one-third of the Senate and over 50 congressmen. This was the first time in U.S. history that a bill drafted by a black organization was introduced into Congress.

Becoming the chairman of Core in 1968, the organization took a turn away from inter-racialism and toward an increasingly conservative black nationalism and capitalism. During the 1970s, Innis and CORE supported the murderous Ugandan dictator and Nazi sympathizer, Idi Amin, stating, “Ugandans are happy under General Amin’s rule of Africa for black Africans” and terming the despot’s decision to expel 50,000 Asians from the country “a bold step.”

Seeking to enhance and build on the black pride movement of the mid 1960’s, Roy Innis and a CORE delegation toured seven African countries in 1971. He met with several Heads of State, including Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere and Liberia’s William Tolbert. Just two years later, Roy Innis became the first American to attend the Organization of African Unity in an official capacity. That same year he participated in a televised debate with Nobel Physicist William Shockley on the topic of black genetic inferiority.

Roy Innis’ involvement in criminal justice matters spans his entire career in CORE, and is filled with controversy. Innis has lost two of his sons to criminal gun violence. While Roy Innis was moving upward in the CORE hierarchy, tragedy struck his family. On April 15, 1968, his 13-year-old son, who was playing with his brother outside a Bronx apartment house a short distance from his mother's house, was shot by an irate postal worker. "It was a very sad thing to have to explain to a father," the detective who informed Innis of the shooting told the New York Times . "The kids were just playing. They were just horsing around."

In his eagerness to defend the 2nd amendment, Roy Innis has often taken the public stance of defending criminals using weapons, even when it is politically polarizing. It was his investigation in the early 1980’s that led to the uncovering of evidence that Wayne Williams was not solely responsible for the Atlanta Child Murders. His defense of victims’ rights to defend themselves led to his support and involvement in highly publicized cases such as publicly defending the “subway vigilante” Bernhard Goetz who shot and killed four African American youth on a subway in New York City in 1984.

Roy Innis remained in the public eye throughout the early 1990s. In a 1991 Wall Street Journal editorial, "Gun Control Sprouts From Racist Soil," Innis argued that banning handguns would keep guns out of the hands of black families in high crime areas who needed protection. He stated in an interview with Robert Santiago for Emerge that "CORE is the only group with the courage to admit the obvious, that black folks, minority folks, folks in high-crime areas need to arm themselves legally."

Don't miss a single page. Find everything you need on our complete sitemap directory.

Listen or read the top speeches from African Americans. Read more

Read about the great African Americans who fought in wars. Read more

African Americans invented many of the things we use today. Read more

Thin jazz, think art, think of great actors and find them here. Read more

Follow the history of Black Americans from slave ships to the presidency. Read more

Olympic winners, MVPS of every sport, and people who broke the color barrier. Read more

These men and women risked and sometimes lost their life to fight for the cause. Read more

Meet the people who worked to change the system from the inside. Read more

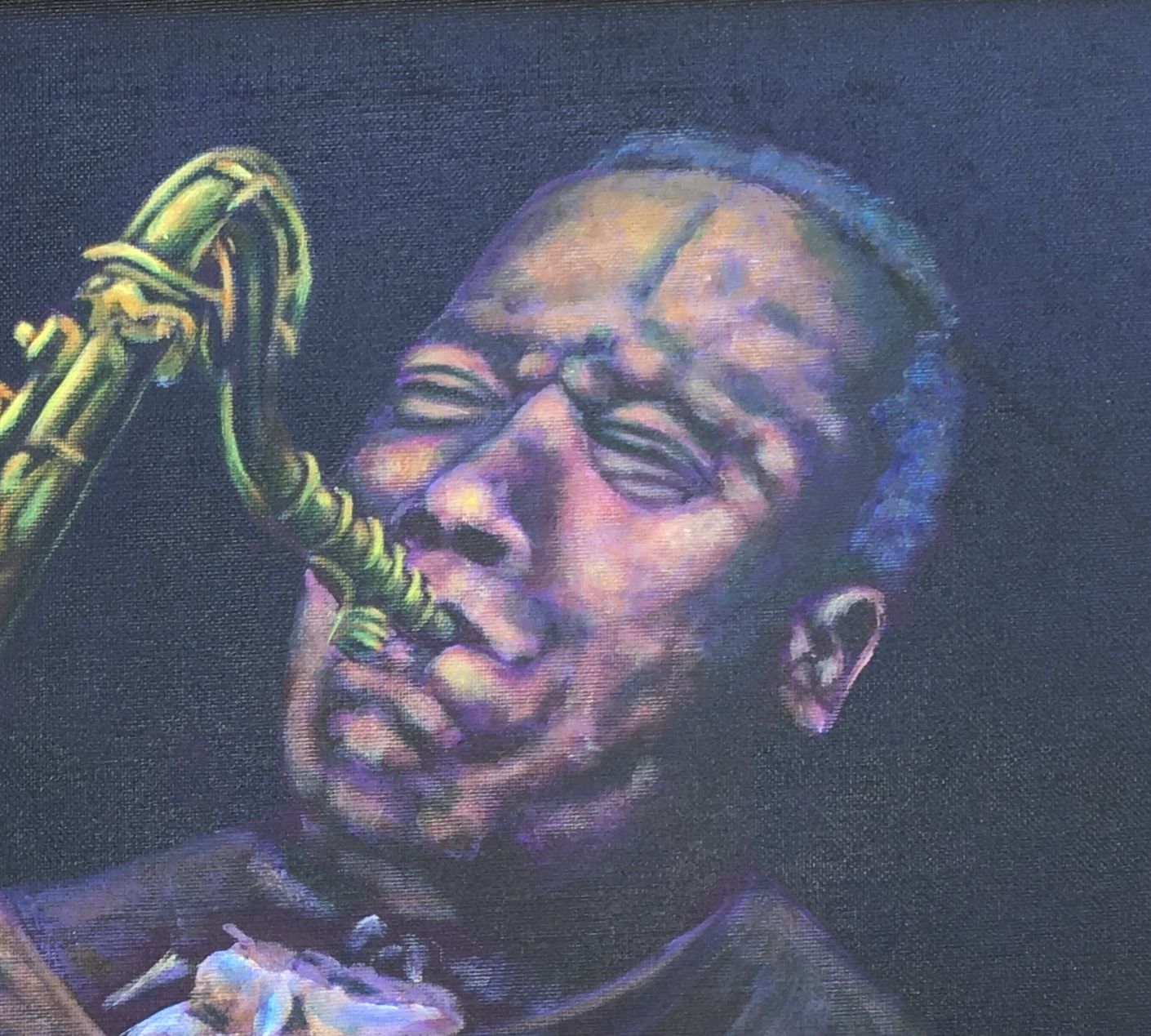

Visit my RedBubble page and use Michael Arnold Art to create greeting cards, T-shirts, mugs, and more.

The variety and impressive numbers of mammals, birds and marine wildlife in Alaska draw visitors from all over the world. For some travelers, Alaska is wilderness, at least compared to what they may know from back home. The pristine wilderness of Alaska is, perhaps, the last vestige of thriving populations of North American wildlife. Where else can you see polar bears, bald eagles, blue and humpbacked whales, gray wolves, grizzly bears, orcas, lynx, moose, and hundreds of other rare and endangered species in their original and undisturbed natural habitats?

Enjoy our website filled with original signed acrylic paintings by award winning Artist Michael Arnold. Located in Citrus County Florida, Michael Arnold is a the editor at the Citrus County Chronicle. When he's not busy being an editor, he is an avid artist who enjoys painting in a variety of styles. We hope you take the time to click on each image to see a larger view and to learn what the artist, Michael Arnold has to say about his paintings.

As dog owners and people who care deeply for animals and wildlife, we wanted our Dog Encyclopedia to be a website that could empower pet owners to create the most positive, loving environment for their dogs. Dog Encyclopedia realizes that owning a dog is like adding a new member to your family.

Floridian Nature has everything your are looking for in Florida nature. The wildlife of Florida is rich and varied, yet most of us are familiar with only a dozen or so species: the "well known endangered species such as manatees and panthers; those, like raccoons and squirrels, that have adapted to urban environments; the frightening alligators and black bears; and those like the armadillo who can't seem to cross the road. Yet they are just a few of the many animal species found in Florida.